Building of Permaculture Earth-Shelter Cabin

- Megan Christian

Picture Summary: Clay-slip Straw Cabin Build

The cabin is available for overnight stays through our HipCamp listing. Enjoy the cabin and visit this Midwest Permaculture design site at CSC in Stelle, IL. Tours available.

Our First Cabin is Done - Completed 2020

We guided the design and construction of the first of several cabins on the CSC’s 8.7 acre design project. The cabins are part of a long-term sustainability plan for this land.

Why is it called an ‘Earth Shelter?’ Because it is made from the earth right beneath our feet here, just 50′ from the cabin.

The goal of the CSC permaculture design is to learn how to build and live more simply so that we might create a more sustainable future. Many people are interested in tiny homes, as are we, so a small cabin made from mostly natural and locally sourced materials became an obvious early project.

With all the workshops we offered, over 150-people got first-hand experience in natural building as they helped build this cabin over a 6-year period. Here is the basic information on how the cabin was built from the foundation up.

Why the Cabin and the Size?

The creation of this cabin was inspired by Henry David Thoreau. He lived in a hand-built cabin on Walden pond for close to two years where he reflected upon and wrote about his ideas of living simply in his classic book, Walden. Our appreciation for his thoughts on living close to nature encouraged our efforts to build a cabin that had integrity and longevity. The square footage of our cabin is almost exactly that of the one Thoreau built on Walden pond from recycled and hand-cut materials for $28.12 in 1845.

Why use clay?

The first rule of thumb in permaculture construction is to seek out ways to use the most readily available materials on site. In Stelle, we are sitting on an ocean of clay.

Clay soils are typically slow to drain, hard to dig through, and make a muddy mess during the rainy season. On the upside, however, clay shines in its ability to bind loose substrates like sand, stone, or straw into a solid mass once it dries. The trick with building using clay, in the long run, is to be certain to keep it dry.

So for all of the cabins we design and build, clay will be a major component as it comes right from beneath our feet. The most common ways to build with clay are by creating:

To decide which method would work best in our situation, we assessed the overall goals for the structure. It had to:

- Last for a very long time

- Have a high R value (good insulating qualities)

- Have the majority of materials used be locally/sustainably sourced

- Withstand our humid climate and slow-draining soils

We compared our options. Solid clay has the tendency to crack since it expands and contracts according to moisture conditions. If we were to create a structure from clay brick, the humidity present in the air here would likely damage the clay unless the bricks were fired in a kiln.

What about cob? Unfortunately, it has a very low R-value. A 1-foot thick wall of cob has an R-value of approximately 3. (for comparison, your average house walls are rated R13-23.)

A 1-foot clay-slip wall, however, is rated R18-24 since it is predominantly straw which is a good insulator as it traps air. The low ratio of clay also reduces the likelihood of cracking. Using straw as a primary building material was also advantageous since compared to sand it is very lightweight and relatively easy to work with. Plus, we could source it locally from a farm just 6 miles down the road.

So we settled on clay-slip straw and started to dig the foundation.

Rubble Trench

As mentioned earlier, clay is very hard to dig through!

Rubble Trench with a 4" Perforated Drain Tile

As we started to fill the trench with gravel we added a 4″ drain tile around the bottom, providing a channel for water to exit. The drain tile exits the foundation underground, always flowing slightly downhill, to where it finally exits above the creek. This is referred to as ‘draining to daylight’. We’ll never need a pump to get water out of the foundation. The end of the tube is covered in mesh to prevent small animals from entering.

Bond Beam

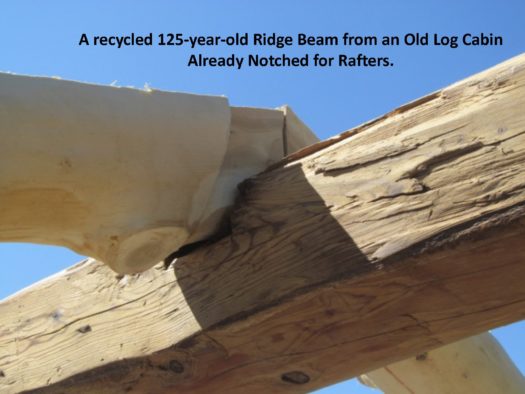

Post and Beam Frame

Insulated/Steel Roof

Why such a large overhang on the roof?

Since we are building with biodegradable materials (straw and wood) it is essential that everything is protected from rain and excess moisture. The common phrase used in designing such a building is to always have a “big hat and dry feet.”

Stem Wall

Clay-Slip Straw

Hassan Hall is our builder supreme. Other than the foundation, timber framing, and roof, he guided the building of every other aspect of the cabin. It is his experience and skill that made this cabin the high-quality gem that it is. THANK YOU HASSAN!

Earth/Clay Plaster Wall & Floor Finishes

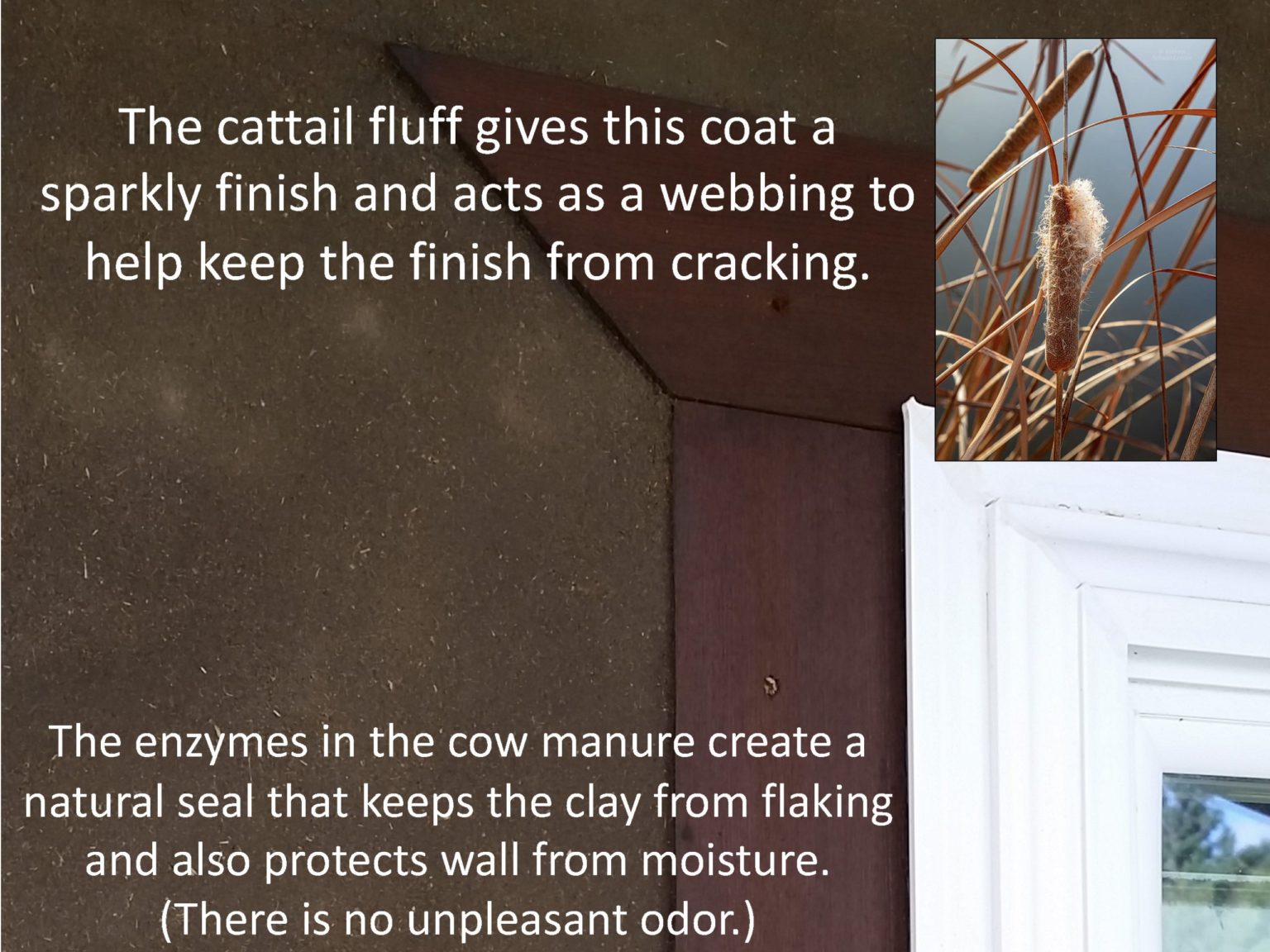

Then we applied the finish coat.

Flagstone Patio

The Finished Cabin

We are grateful to Hassan Hall of Dancing Rabbit Ecovillage, for taking on the role of technical designer for this project. His expertise made this building process a real joy. His talent in understanding not only the technicalities, but the overall aesthetic and feel of natural building design is on full display everywhere you look in this cabin. Thank you again, Hassan. His website is here.

Now that it’s finished, The Earth Shelter Cabin is available to book through Hipcamp. Come and stay to experience what it’s like to spend time in an off-grid, naturally-built shelter. While here, if you’d like to learn more about our larger permaculture project, a short tour can be arranged. See our Hipcamp listing for more info.

We hope you gained some useful and even encouraging information through this post.

Cheers…

Bill Wilson – Lead Designer/Teacher at MWP

Megan Christian – Key Design/Teaching/Communications Support

August 2021

Updated September 2024

6 thoughts on “Building of Permaculture Earth-Shelter Cabin”

What a beautiful cabin. Well done. I am working on a hybrid greenhouse and found your incredible, well articulated, easy to read timeline of your process. It is so helpful! I am considering a bond beam on the rubble trench, after a lot of thoughts about steering away from concrete. It has made me feel like it could be an environmentally friendly, yet cost effective way to make the building feel more secure and add a good base to frame off of. I can’t say thank you enough for the great photos. I’m sure this will be very helpful.

Cheers!

Great project, Bill. Kristi and I are midway through the construction of our new house. Straw-clay walls are complete, and earthen floor will finish it off next spring. Green roof completion after that. Be sure to contact us if you get up this way.

Thank, lots of interesting and creative concepts here. there is a lot of labor with these materials, but you are substituting labor for more expensive building materials. We should not turn our backs completely on modern materials — glad you used a metal roof.

Does the house have electricity? Solar panels? An inside root cellar / tornado shelter might be a good addition.

Thanks for the blog.

Thanks for sharing the design/build pics! Very instructive as Julie and I will be constructing something similar in Hot Springs one day.

It is our pleasure! That’s great to hear.

Beautiful!