Chinampas Gardens

- Brianna

Why Chinampas Gardens are part of This Permaculture DesignChinampas Gardens are artificial islands or peninsulas created by scooping nutrient-rich lake, swamp or pond muck into a woven cage so that crops can be grown above the waterline in a wet environment. Within this simple design, several unique functions are accomplished at once: a micro-climate that prevents early frost damage; an extremely productive soil that is mostly self-sustaining; a self-watering system created by water wicking in from the sides as moisture evaporates from the surface of the beds; and the growing of plants and fish within the same area. In Particular we want to:

|

|

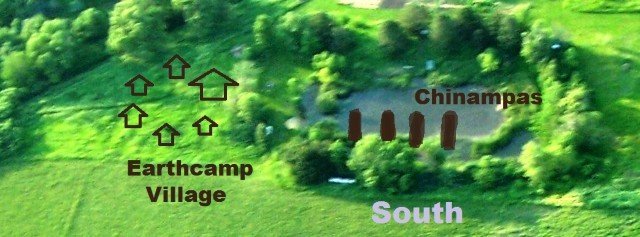

Chinampas Gardens ExplainedThere is plenty of room across the south shore of our pond and we plan to build three to five Chinampas extending out into the water like peninsulas for about 25 feet. They are located close to Earthcamp Village so that students, interns and/or guests camping in the cabins can quickly and easily access the chinampas gardens for food, fishing and enjoyment.

About the Stelle Pond When our community of Stelle was built, a small pond just outside of town was dug so that residents might have some sort of wetland close by. Over the years we have watched it mature and recent testing has revealed that the water is amazingly clean and free of agricultural chemicals. The watershed that feeds this pond is all on the Stelle community property. But as with most ponds, with time there has been some silt buildup close to shore which creates an ideal environment for cattail and other shore loving plants.

History of Chinampas

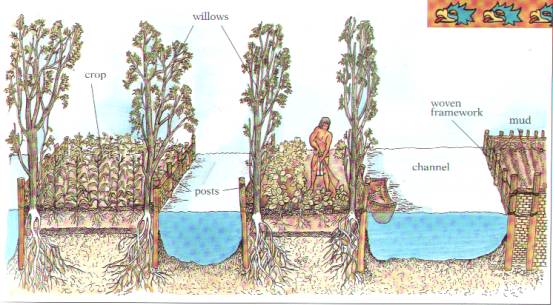

How and Why they were so Productive As in good permaculture design, Chinampas work by turning wastes into resources while stacking functions to maximize yields and minimizing work. After a plot is staked out into low ground or shallow ponds and lakes, a fence was woven between the stakes to create a cage or large basket that the farmers could then fill with the surrounding sediment and various forms of vegetation. The beds would be built high enough to become permanently above the high water mark and willows would be planted on the edges to protect the banks from erosion over the long term for when the posts rotted. Channels were maintained between the Chinampas for canoe access and for the growing of fish and water fowl.

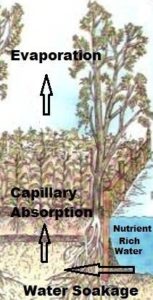

Since water is always available to the bed, as water evaporates from the surface it is replaced by capillary action from below. A chinampas never has to be watered once a plants root systems are down. The grower never has to worry about drought or watering again. And because the ground is permanently moist by the capillary action of water being pulled upwards by ground evaporation, soluble nutrients stay suspended and available to the plant roots. What is created is a perfect root zone environment…all the time!

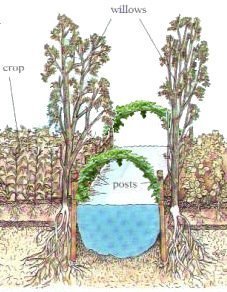

The Edge Effect In a good permaculture design we take advantage of the areas where one system comes into contact with another (the edge zone) as this tends to be an area of greater activity and productivity. For example, where the water meets the banks there will be plenty of plants that could grow right along the bank or just into the water that would provide a unique species for food (humans, fish, ducks) or simply biomass for increased garden fertility. Insects attracted to the edge plants become food for fish. Ducks eat the plants at the shore. Their droppings becomes food for the fish. All remaining residue and the fish poo sinks to the bottom to become fertile detritus that can be scooped up annual and added to the garden beds. And because the fish are raised in channels they are easy to harvest with nets. Because ducks and geese are part of the system they are trained to help with keeping the banks weeded as well as working in the garden beds. They are great slug and weed eaters. Trellis over the Channels In some areas, arching trellises were extended over the narrow channels and vining plants such as squash, cucumber and beans were planted so that their yielding crop could be harvested directly into a canoe, paddled to shore for unloading, and then return for more. An Amazing Microclimate Combining the beneficial effects of surrounding water and trees to a growing environment is also a brilliant strategy. The water in the channels maintains a more constant temperature than soil, so the entire chinampas area establishes a micro-climate that greatly ameliorates the effects of frost damage — a simple method of season extension that does not require expensive row covers or greenhouses. Trees not only held the banks in place and provided shade and some fruit for growers, they also protected the chinampas gardens from high winds on gusty days while holding in warmer air underneath the canopy on cold days. Together, these created a higher temperature and humidity level than the surrounding farmland which greatly mitigated frost damage.

“Creating channels of warmer air, the morphology of raised fields and associated canals can raise air temperatures as much as Maintaining the Soil Caring for the fertility of the soil in this design is almost self-sustaining. Simply scraping up the detritus on the bottom of the waterway and adding it to the soil is all that needs to be done. Detritus is the organic matter (leaves from garden plants, weeds, duck and fish poo) that falls to the bottom of a pond and breaks down. One could make the analogy that it is simply another way of composting waste materials into soil. Benefits of Chinampas Gardening

A more perfect example of stacking functions in a permaculture system can rarely be found. Fish, fowl, and water plants could be harvested from the water channel and vegetables, fruit, and lattice-grown vines from the bed itself.

So….how can you apply chinampas design into your own system at your home? Let us know how it goes and share your stories on the Midwest Permaculture networking site.

This Article Co-Written by Bri Wrench and Bill Wilson |

Bri Wrench earned her Permaculture Design Course Certificate from Midwest Permaculture in the fall of 2012 and currently homesteads on a small, rented farm in central Ohio. She and her husband Kenny are looking to buy property to start a permaculture demonstration farm. |

Bill Wilson is a permaculture teacher, designer, and the co-founder of Midwest Permaculture. |

[contentblock id=10]

The genius of this system?

The genius of this system?

25 thoughts on “Chinampas Gardens”

Hey Bill,

Any update on the Chinampas?

I’m thinking of trying it in Minnesota and looking for someone who has successfully done it.

Thanks.

Chris

Hi Chris.

The pond was drained and dredged last fall and is in the process of refilling now. This is a group design project here so each element in the design needs resources (time and money) devoted to it and the chinampas are not at the top of the list. It will be another year or two I’m thinking. Wish we had some more helpful information for everyone but we’ll get there. Slow and steady solutions. 🙂

I am very interested in finding out the status on your Chinampas project at this time. I do hope that all your other projects are moving towards success as well.

Hi Dee,

No progress on the Chinampas project yet. The first step is to rehabilitate the pond. Luckily, we got some great pond building experience at our Bending Oak project in Ohio last fall. Hopefully, we can work on our pond this summer/fall.

Hello,

How is this project coming along?

It is very interesting and I would like to build some “Chinampas”.

Hi Scott. The plans are still there but decided that the pond needed dredging first as it has been silting in for 40 years. After we get it cleaned up we will likely move forward with the chinampas.

Bill

I live in southeast Texas. I have a pond on lot next to me and the creek that feeds it runs behind. I ran across chinampas years ago. Glad to see more research done into it. July and August dry everything out. I am wanting to have small islands in back where runoff from neighbors can make back useful and landscaped instead of semi-marsh and then dry and caked. Neighbor is sort of landscaping (scraping?). I had read about smaller versions it seems. I tried to click on link for poster but it is no longer working. I only have about an acre and half so small version work best. Liked the arching idea. About how deep are the canals? Tree more likely on south end here for some shading. Thanks, Penny

Two thoughts:

1. I remember noticing on Google Earth LOTS of ancient “canals” along the Eastern and Southeastern coasts of the United States. Perhaps they were Chinampas Gardens.

2. On your pond, wouldn’t you want to have the anchoring canopy trees on the ]North[ end of each Chinampas Garden? Permaculture principles suggests the taller trees would be on the North end, the shorter to the South, right? This would require your Chinampas Gardens to extend from the northern, not the southern shore.

Good thoughts Jesse.

Don’t know about the canal in the US but they certainly sound interesting.

And you are spot-on regarding the shading effect of trees upon the chinampas depending upon where they are placed. We are designing our swales to come off the south edge for two basic reasons. 1. the bank has a shallow slope compared to a sharp drop-off on the north bank so it will be much easier to build from. 2. The south bank is the longer run so we can fit 3 wide or 4 narrower chinampas along it.

Regarding the shading, we will be growing mostly willow along the sides and ends which we will coppice on a regular basis meaning that the trees will never be more than 6-8 feet tall while the roots can become substantial, holding in the banks.

Thanks for asking…

“chinampas” are commons since antiquity in Europe, using the chinampa word and wondering if it is suited to northern regions is strange. Using this word is fine, but at least one should know that those systems are found earlier in Europe than in the Mayan culture.

Look for example at the Hortillonnages d’Amiens. Total mastering of the concept, at least one millenar before the Mayans that is. Why not call it “hortillonage” then… But more simply, that’s what market gardening is about historically. It is the action of mar-sh gardening. It’s a ‘floating’ garden. Only watter-clogged places were left after everything else was put in grain or pasture. So, those wet aera are mounded, canalized, the mounds are then cultivated, giving birth to the expression “mar(sh)ket gardening”.

This is very cool and interesting, thanks Ion! Through the little bit of research I have done, I’ve only run into French sources and google translate can only help me so much. Do you have any resources or can you point me in the right direction where I can research these Hortillonnages further. I would love to know more.

Raised or drained field systems are widespread across the globe. Generally, chinampas refer to the Central Mexican/Aztec systems because the term is based on a Nahuatl word for the fields. In the Maya area they usually stick to the term raised field systems. If I was to build raised field beds in my backyard modeled after Aztec chinampas I would probably refer to my backyard fields as chinampas because of my familiarity with the term. Anyway, many different systems whatever they are called have similar important and productive functions. It is always interesting to learn about different examples about wetland agricultural systems.

Thanks, just googlebook it(https://www.google.com/#q=hortillonnages+garden&safe=off&tbm=bks)

Here some links :

http://books.google.fr/books?id=PWPL3ldrflkC&pg=PR13

http://books.google.fr/books?id=YVLU-_6KcSoC&pg=PA24

Actually hortillonages are running at maybe 2% production capacity the rest is just tourist attraction & a ‘floating suburb’ with pretty flowers competitions.

I remember finding chinampas awhile ago now, and i was doing some thinking and remembered this post. In this bio-region and for what would grow here, it almost seems like a chinampa variation would be better suited. In the tropics, for at least half the year the soil is saturated or even super saturated, its make up and support systems expect and work with that kind of scenario. Here in the midwest, swampy areas form, and eventually the area’s draining improves and water shedding increases, as well as fibrous material fills in the ‘whole’. Pons or small lakes stick around for some time. your distance into the pod seems right, i think 10′ wide beds would be the minimum, with really wide growing area, 4′. Which got me to thinking, a keyhole design would almost be better suited to this climate region. Having half circles or something, semi-circular maybe, but, i’m having a hard time thinking of how to keep the soil from being anaerobic in that situation. I mean, large rock bottoms, and some soil aggregate, expanded clay fired clay maybe and all compost/topsoil, but i still see that as tricky. As far as install. i dunno, any water construction i know of always has to dry the area first, levy/wall, and pump the water out.. a large barge?? 😀

Thanks for these ideas Evan. We have not decided yet on exactly how we will construct these nor have an certainty about how they will work… so… all input is welcomed. Our focus this first year is putting in our first linear food forest (it’s in now but needs some care) and building our first earth shelter (scheduled to begin next week).

Life is full and exciting… Cheers… Bill

Good luck with your Midwest chinampas project! The Aztec plots were relatively thin (3-4 meters wide) but varied incredibly in length (up to 500-1000 meters long) and took many forms (U-shaped for example). The thin Aztec beds would not have been tree-lined like the historic and modern fields. Also, splash irrigation from canoes would have been common in the dry seasons so they weren’t actually self-irrigating. I’ve digitized 1,000 hectares of the Ancient beds for my dissertation so chinampas are on my mind. In PA, we regularly add pond muck to our gardens so I imagine warm season chinampas in the Midwest will be productive. Greg

Hi Greg…

Very nice to have your learned comments and ideas. The splash irrigation makes a lot of sense, especially with young plants. We are looking forward to experimenting and learning as much as we can from this project. Please weigh-in whenever you like.

Is there a place on the net where we can read or visit your dissertation? I’d love to see it.

Regards… Bill

Hi Bill, I defend in 2 months and will be submitting the final version shortly after the defense. I can send you a copy of a Society for American Archaeology poster before I present it in April. It’ll provide a good project overview, maps, statistics and graphics. Regards, Greg

Would love it… Thanks Greg.

Here’s a link to my SAA poster that provides some empirical data and analysis of Aztec chinampas in Lake Xochimilco. Greg

http://www.personal.psu.edu/ggl103/LunaSAA2013poster.pdf

Thanks much for the poster Greg.

Have read through it and enjoyed it greatly. Might you be willing to join me in a phone conversations at some point with a few of our other teachers to walk us through your research?

And may I make a hard copy of your poster to share with our future Permaculture Courses?

Sincerely appreciate you sharing this with us.

Regards…. Bill

Sure Bill, Just email me at . You can tell from my poster that I’m into the archaeology and spatial layout of the ancient system. I haven’t focused on modern inputs into the more recent systems that continue to make chinampas a very productive agricultural system. Feel free to print out the poster. Greg

Can you give us more info on the chinampa project, specifically what will be used as the base or frame. The black locust trees growing near the pond could be sourced as a rot resistant wood to anchor the chinampas. As I recall one of the students from the MREA PDC course in 2008 had looked into chinampas for his Michigan site. I don’t recall if he had ever implemented the ideas.

Great question and comment Bryce…

Although we have added chinampas to the overall design, the exact details on how we will go about building them is still open for discussion and brainstorming.

We invite anyone interested to weigh-in on this. Here are some of the considerations we still need to design for.

1. What will we use as pilings to form the initial sides or basket? Wood? Steel? Plastic? What will the diameter be and where will we source it from? Remember, we have almost no straight trees around here. We will likely have to import something.

2. What will be the lengths of the piling and how do we go about pounding them into the pond muck? There in nothing to stand on once we get into the water. To note, the chinampas will extend out into the pond about 20 feet and to a depth of about 6 feet, then the piling will need to be driven into the bottom 1-3 feet and the finished bed be will need to be above the high water mark by at least a foot. In other words, some of these pilings will need to be 10 feet long.

3. And what will we use to weave between the pilings to hold the muck in for a long period of time before we establish the banks? And how do we do the weaving under water?

4. Will we even use pilings or is there some other method or materials we can use such as sheets of treated plywood, aluminum or steel?

5. And finally, once the chinampas are built, what will we plant on the sides to hold the banks in place for decades to come? Willow, mulberry, ash and black locust grow well around here (and black locust is a good nitrogen fixer).

If you have any thought on the above please share them. We welcome you as part of the design team…!!!

why don’t you dig the chinampa system into the banks of your pond?

you don’t have to bring in soils & it would be easier to construct like a dry dock and then knock down the retaining wall at the end

work with what you have